Loud and constant is a myth that Chicago is dangerous and unkind. People love drama, especially if they’re not the ones getting shot at or having their car jacked. It reverberates in the echo chambers of modern handheld news infotainment. It wears on you. Sometimes I believe it. Sometimes I don’t. But I know this: the noise can drive you mad, if you let it, and if you don’t find silence, it won’t find you.

I carve out time to sit, to see what’s good, to remember. September is a good time for that. There’s a place between night and day where the world forgets itself, where water and sky meet, somewhere between the last cry of night and the first breath of day, a place where the world forgets itself where there is still water, and there is still sky, and the thin jagged place where the two meet.

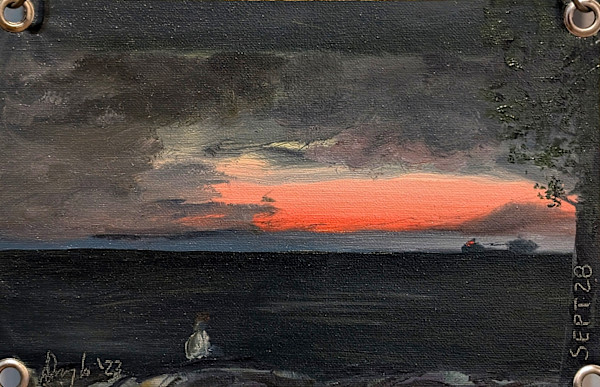

It was two Septembers ago when I first began the ritual. A challenge, really, of my own invention. Thirty Days, Thirty Sunrises. I had never painted outdoors before. Never dared it. The very idea of it—raw canvas, thick oils, the scent of turpentine and lakewater mingling in the air—felt romantic, but also deeply uncomfortable. I’d always preferred the safety of the studio: controlled light, familiar brushes, my smartypants speaker thingy playing a bespoke mix of jazz, classical, and medieval just loud enough to hush my thoughts. Indoors. Controlled climate. Nothing blows away. No goose poop underfoot. No splashing waves sending lake mist all over your oil palette.

But this was different.

Every morning, just before five, I’d leave the warm cradle of my apartment—kit in one hand, canvas under arm—and walk the three blocks to Promontory Point. It’s a flat peninsula of green space and old trees jutting into Lake Michigan like the prow of some ship run aground. It’s where joggers jog, dogs drag their people around, open water swimmers practice their craft, and the sun comes up like it’s got something to prove. At that hour, the city is still sleeping or dreaming, and the Point is quiet, a little solemn, a little sacred.

I painted there. Every morning. September’s days like pearls on a string—some gray and thick and clouded, others so clear they cut the breath from your throat—and I was there for all of them. Painting. Fast. Too fast. No time for the careful weeks of studio quiet, no time to stand back and squint and revise. The sun does not pause for painters. It leaps, it screams, it bleeds across the lake and then it’s done, gone, hidden behind some bank of iron clouds, and you are left with only what you caught in those short minutes, a breath held on canvas.

Pink, one day. Gunmetal the next. Sky like molten gold or copper or the ash at the edge of fire. The horizon a place of constant betrayal—just when you think you’ve captured it, it changes. The sky shifts—rose, lavender, chalky blue. And then, suddenly, light spills across the horizon like a secret being told too fast. You mix the right tone, then it shifts. It was beautiful, yes. But also cruel. A cruel dance, really—me chasing the color, trying to hold on to something that isn’t meant to last. Olive one morning. Pale orange the next. Some days, clouds blotted out everything before I’d finished the base layer. Other days, the light was so vivid it felt artificial, like theater. I never quite captured it. Not exactly. But I tried.

And yet it was not the painting alone that made the experience sublime. It was the people. They’d stop by sometimes. Ask questions. Nod appreciatively. Or just walk past like I was part of the scenery. Which I guess I was, eventually.

There was the woman with flaxen hair who jogged three laps around every day, regardless of the weather. On Tuesdays a group of ladies with headlamps on a power walk in the dark. Bicycle Man had his own walk-on music, cheerful and loud, flourescent vest and flags on his bike and a greeting of “Hey, Paint Man!” to me as he passed. The sunrise swimmers, a loose collective in wetsuits even when the water looked like it wanted to kill you. There was an impatient young man with a fishing rod, casting, moving, casting, moving. And another who simply sat on the same rock, coffee in hand, eyes fixed on the horizon. The old men with thermoses. The runners who nodded. The women walking dogs who wore sweater vests.

It was the quiet shared space of strangers in the dawn. Strangers who nod as if they’ve known you for years. Not friends, not in the ordinary sense. But we shared a moment, a rhythm. They saw me, and I them, and in that recognition something passed between us—not words, but a knowing. That we were there for more than habit. A convergence. The collision of water and land and darkness and light. Together we’d discovered a place where time slowed enough to be seen, touched even.

So why did I go? What was I painting for? What were we all doing there, really? All those walkers and runners and swimmers and painters? I think we were trying to slow time down. To remind ourselves that not everything is noise and urgency. Trying to believe, just for a second, that we weren’t living in a collapsing empire of screens and honking and existential dread. We were witnesses. Participants in the daily miracle of the sun doing the same damn thing it’s done for 4.5 billion years.

That’s what I want my art to do. Not just to depict, but to preserve. The feeling of a September morning. The hush before the day begins. The quiet miracle of light returning.

Anyway, that’s the point of art, I think. To say: “Look at this. It was beautiful. It happened. I was there.”

That’s what art is for. Even if it only lasted a minute.

- Subject Matter: landscape, sunrise, installation

- Collections: 30days30sunrises