Chaire

A tea caddy, usually ceramic, used to hold strong tea at a tea ceremony. Its dimensions vary, ranging from 3-15cm high, with a diameter of about 4-8cm. First brought to Japan in the 13c, the most valued chaire were made in Southern Song and Yuan China and thus considered *karamono 唐物 in Japan. Usually a chaire is put in a bag shifuku 仕覆, made of very fine material, such as high quality silk gold brocade, damask or striped silk called kantou 間道, from China, and carried into the tea ceremony room. The gorgeous material of the bag was also appreciated at a tea ceremony. Chaire were made in Japanese kilns from the Momoyama period. For the parts of the tea caddy. The methods of making the bottom of the tea caddy were as follows:

1 itokiri 糸切り: The clay bottom of the tea caddy is separated from the potter's wheel by using string that leaves a spiral mark. Japanese and Chinese tea caddies can be distinguished by these marks. Seto 瀬戸 objects have a right ward string cut, considered the normal string cutsince a potter's wheel turns clockwise, but Chinese objects have a left-ward side string cut because their potter's wheels turn counter clockwise.

2 uzu-itokiri 渦糸切り: If clay is removed from the potter's wheel with a nail or spatula, a spiral pattern will result from a gentle, extra turn of the wheel. This spiral is an important feature in the tea ceremony.

3 maru-itokiri 丸糸切り: Related to itokiri 糸切り. A string line, which is created on the bottom of the tea caddy when it is removed from the pottery wheel, this technique sometimes used for the most exquisite of tea caddies.

4 wa-itokiri 輪糸切り: To carve many concentric circles with a thin needle on the bottom of formed clay. The word may also be used for the pattern itself.

1 itokiri 糸切り: The clay bottom of the tea caddy is separated from the potter's wheel by using string that leaves a spiral mark. Japanese and Chinese tea caddies can be distinguished by these marks. Seto 瀬戸 objects have a right ward string cut, considered the normal string cutsince a potter's wheel turns clockwise, but Chinese objects have a left-ward side string cut because their potter's wheels turn counter clockwise.

2 uzu-itokiri 渦糸切り: If clay is removed from the potter's wheel with a nail or spatula, a spiral pattern will result from a gentle, extra turn of the wheel. This spiral is an important feature in the tea ceremony.

3 maru-itokiri 丸糸切り: Related to itokiri 糸切り. A string line, which is created on the bottom of the tea caddy when it is removed from the pottery wheel, this technique sometimes used for the most exquisite of tea caddies.

4 wa-itokiri 輪糸切り: To carve many concentric circles with a thin needle on the bottom of formed clay. The word may also be used for the pattern itself.

Raku Kichizaemon Lineage Collection

The Raku family of potters has a centuries-long ceremonial bond with the Urasenke school of tea. As the designated chawan artisans among the “Senke Jissoku” (the ten traditional craft families serving the Sen tea schools), the Raku lineage has crafted tea bowls favoured by generations of tea masters. From the founding generation (Chōjirō under Sen Rikyū) onward, Raku bowls have been treasured in chanoyu for their wabi simplicity and ability to enhance the tea experience.

Urasenke, one of the three main Sen families, in particular cultivated a close partnership: many Raku bowls were made to suit Urasenke preferences, and in turn Urasenke iemoto (grand masters) would often bestow poetic names (mei) on especially distinguished bowls.

Urasenke, one of the three main Sen families, in particular cultivated a close partnership: many Raku bowls were made to suit Urasenke preferences, and in turn Urasenke iemoto (grand masters) would often bestow poetic names (mei) on especially distinguished bowls.

Shigaraki Yaki

Shigaraki ware, originating from Koga town in Shiga Prefecture, holds a venerable position among the Six Old Kilns of Japan. Its roots can be traced back to Juko Murata (1423-1502), the esteemed founder of the tea ceremony, who valued the understated beauty of unglazed pottery and the simplicity of Wabi Sabi aesthetics.

Shigaraki ware boasts distinctive characteristics, encompassing a range of colour shades and patterns from deep reds and browns to delicate pinks. These captivating hues are achieved through firing with fire-resistant coarse soil, which imparts a unique touch to the pottery. The dark tones that emerge from the natural glaze on the scorched portions of Shigaraki ware, affectionately known as rusty glaze, are highly prized and deeply appreciated for their inherent charm and beauty.

Shigaraki ware boasts distinctive characteristics, encompassing a range of colour shades and patterns from deep reds and browns to delicate pinks. These captivating hues are achieved through firing with fire-resistant coarse soil, which imparts a unique touch to the pottery. The dark tones that emerge from the natural glaze on the scorched portions of Shigaraki ware, affectionately known as rusty glaze, are highly prized and deeply appreciated for their inherent charm and beauty.

In 1930, fragments of Shino tea bowls from the Momoyama period were discovered in Kani City, Gifu Prefecture. This discovery of unknown ceramic history sparked increased interest in ancient ceramics across Japan. Craftsmen from various regions were captivated by Momoyama ceramics and began efforts towards classical revival. In Shigaraki, two potters devoted themselves to the revival of ancient Shigaraki pottery: Rakusai Takahashi III (1898-1976) and Naokata Ueda IV (1898-1975). Their Momoyama-style stoneware, called "Hechimon," initially received little local attention. They continued to reproduce the techniques, and their distinctive Shigaraki ware was designated as an Intangible Cultural Asset of Shiga Prefecture in 1963. Their achievements influenced future generations, leading to a flourishing of many artists in Shigaraki who inherited the traditional techniques of ancient Shigaraki during the 1970s.

Takatori Yaki

Takatori ware is a tea pottery kiln that was developed in the Kyushu climate by tea masters such as Kuroda Josui and Kobori Enshu, and is known as one of the seven Enshu kilns, and as the official kiln of the Kuroda clan in Chikuzen. After Toyotomi Hideyoshi's invasion of Korea, the Bunroku and Keicho Wars, which were even called the War of Pottery, many potters came from Korea, and Hagi in Choshu, Karatsu in Hizen, and Takatori ware was born in Chikuzen. Since then, it has produced many famous items and wares, and has continued to live on in Japanese tea ceremony culture, and it has been said that "Takatori is in Chikuzen."

The kiln was opened after Kuroda Nagamasa became the lord of Chikuzen in 1600 and was founded by the famous potter Hachizan (Japanese name: Hachisei Shigesada), who came from Korea with Nagamasa. They first opened their kiln in the Eimanji residence, then moved to Uchigaiso, Tojindani in Kamiyamada, and Shirahatayama in Iizuka (1630), where they further refined the family's secret techniques, and left the kiln here in 1654.

During this time, the second lord of the Kuroda domain, Tadayuki, sent the eight-year-old father and son to Kobori Enshu to learn the new tea ceremony philosophy of kirei sabi and Enshu's preferred style of tea ceremony, and worked to cultivate more advanced tea ceremony ceramics.

These traditional techniques unique to Takatori were inherited by my grandfather, the 11th Takatori Hassen (Sashichi), who inherited the will of the 10th Takatori Yasunojo (Shigenobu), the last official potter of the Kuroda clan, and passed them on to my mother and me.

The period from Uchigaiso to Shirahatayama is called the Enshu Takatori period for this reason, and it was during this period that many masterpieces were created, including the tea caddies "Somegawa" and "Aki no Yoru," famous for their revival.

After that, in 1665, the Koishiwara Drum Kiln was opened, and four years later, in 1666, the grandson of the first Hachizo, who had been guarding Shirahatayama, moved his kiln to Koishiwara Nakano (now Koishiwara Sarayama), and the Koishiwara Takatori period began. The kiln in Nakano has never been turned off and has continued to protect the family tradition in the mountains of Sarayama, leading to the current Takatori ware 13th generation kiln owner, Hassen. During the Koishiwara Takatori period, the artistic style of Enshu Takatori's beautiful sabi was perfected and further developed, resulting in the creation of an extremely diverse range of works.

Zeze Yaki

Zeze-yaki Tradition and Kagerōen Kiln

Zeze-yaki (膳所焼) is one of the classic “Enshū Nanagura” (遠州七窯, Kobori Enshū’s Seven Kilns) of Japanese tea ceramics . Historically based in Zeze (now part of Ōtsu, Shiga) on Lake Biwa, it became an official shogunate kiln in the early Edo period under tea master Kobori Enshū, producing tea implements (chaire, mizusashi, etc.) famed for their lightness and elegance.

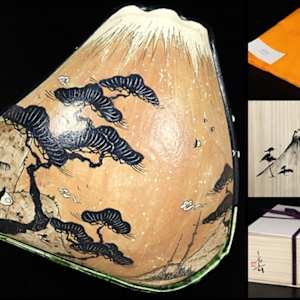

Early Zeze pieces were high-quality stoneware made as gifts for daimyō, often bearing special inscriptions (for example “Ooe” or “Haku-un” names cherished by Enshū). Zeze ware is typically very thin and finely turned. A characteristic glaze is a rich iron-brown that may pool into golden-yellow drips or patches – a look preserved to this day. For example, the Kagerōen chaire pictured above shows the classic dark-brown glaze with a mustard-yellow splash, exactly as 19th-century descriptions note (“dark-brown glaze and a yellow streak”).

After many centuries of activity (and some lapses), Zeze ware nearly vanished by the 19th century. In 1919 local patron Iwasaki Kenzō (岩崎健三) revived the tradition with help from painter Yamamoto Shunkyo and others . He re-established the Kagerōen kiln, and his son Iwasaki Shinsada continued building Zeze’s reputation.

Today Zeze ware is produced by Zeze Ware Kagerōen Co. Ltd., which preserves the old glazes (膳所釉) and forms while also experimenting with new styles. Modern Kagerōen pieces often remain faithful to traditional tea forms but may include enamel decoration or Western influences. Collectors value Zeze ware for its link to Enshū aesthetics; in particular, Zeze chaire of the classic form are sought after for tea practice and historical interest.