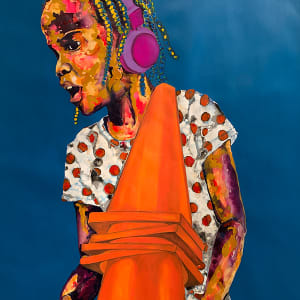

Pikin.

Through evocative, color-rich portraiture and immersive installations, I personify the lived experiences of Black women and girls. Beyond mere representation, each body of work investigates our intrinsic need for space, selfhood, and safety. Pikin. is an ongoing body of work that explores the resilience, vulnerability, and survival strategies embedded in Black girlhood. Each character reflects real and imagined narratives shaped by cultural memory, personal history, and collective struggle.

In my exhibitions, spaces become sanctuaries where the cast of characters depicted in my stained, fluid acrylic paintings can exchange with, respond to, and safeguard one another. The integration of installation and painting welcomes the viewer into the visual narrative, inviting them to contemplate their role as both spectator and spectacle. By blurring the boundaries between artwork, viewer, and space, I aim to cultivate connection and provoke introspection.

Figures like Little Dragon., who must temper her frustration in educational spaces, and Tay., who quietly reflects on the life and loss of Breonna Taylor, are visual testaments to both trauma and triumph. As the collection expands, new girls arrive—growing older, bolder, and finding strength in one another. Their presence insists on care, community, and recognition.

Influenced by artists such as Barkley Hendricks, Faith Ringgold, Simone Leigh, and Ebony G. Patterson, my work engages the transformative power of the gaze—oppositional, reflective, and redemptive. At its core, Pikin. honors the right of Black girls to be seen, to take up space, and to thrive.

MLK Blvd.

MLK Blvd. is an homage, a confrontation, and an invitation. It calls viewers not only to witness, but to locate themselves within the complex architecture of exclusion, memory, and possibility. This body of work interrogates the legacy of redlining and structural inequity through a series of mixed-media collages that depict homes in historically Black neighborhoods—homes that serve as visual records of both systemic abandonment and determined restoration. These structures are layered with the histories of those who built, occupied, and were displaced from them—monuments to the tension between loss and resilience.

Within this narrative, Icky. emerges as a key figure—a character introduced in my Pikin. series exploring Black girlhood. She bridges both bodies of work. Her name comes from a chronic skin condition resembling eczema, caused by the environmental neglect common in poverty-ridden neighborhoods. In one portrait, she stands just outside a home, her hand resting inside its open window—caught in the in-between space of access and denial, belonging and exclusion.

Within the framework of JUST Space, Icky. inhabits the fragile threshold between Gracious Space and Brave Space. Her image captures what Dr. Rudy Jamison describes as “the arrest”—the moment the stranger appears. This work challenges viewers to engage that moment not passively, but actively: Will you invite the stranger? Will you acknowledge the discomfort required to foster equity? Will you risk vulnerability in service of transformation?

MLK Blvd. is also inspired by Screams Echo, a haunting narrative by Bobbie O’Connor that explores the generational trauma caused by systemic violence and economic exclusion. In this story, the fictional lynching of Charlie, the economic strangulation of Daddy, and the real-life murder of Trayvon Martin echo across time. But it is the women left behind—Granny, and her granddaughters Rita, Frances, and Simone—who carry the weight. Their stories reflect the physical and psychological toll of losing Black men to systems designed to limit access and eliminate possibility. These women persist in the very homes and neighborhoods left behind, embodying a legacy of grief, care, and unyielding endurance.

Together, the mixed media collages of MLK Blvd. and the presence of Icky. illuminate the spatial and emotional consequences of structural inequity—while also honoring the resilience of those who remain. These works do not offer resolution. Instead, they pose a challenge: to see what has long been obscured, to interrogate your role in the narrative, and to choose—if only for a moment—to invite the stranger in.

The Hotelmen

The Hotelmen is a tribute, a reckoning, and a reimagining. This body of work emerged from my desire to honor the Cuban Giants—the first professionally salaried Black baseball team—who played in St. Augustine, Florida, from 1885 to 1886. These men were more than athletes; they were waiters, performers, and pioneers who navigated a world that both demanded their labor and denied their full humanity.

My work explores the complex existence of these men, particularly through the figure of Frank Thompson, the head waiter at the Hotel Ponce de Leon and founder of the Cuban Giants. The name Hotelmen recognizes that most Black athletes of that time supported themselves as hotel staff during the off-season. Their lives moved fluidly between service and sport, performance and survival. In my paintings and installations, I attempt to capture that rhythm—the shifting posture between public persona and private self.

Using screenprints inspired by vintage posters, painted wooden pennants, Flagler-era tableware, and reimagined photographs, I reconstruct the fragments of a story too often overlooked. Color is my entry point. “Sharp color contrasts expose the players in visible and vivid hues—at once cool in tone, and then radiant, molten, and sunny” (Brantley, 2023). These color choices are not only formal—they are emotional and historical. They speak to the duality of being both performer and person.

The cakewalk paintings explore this tension more explicitly. As an African American dance that began as satire and evolved into spectacle, the cakewalk embodies the complexity of performative Blackness. Like the Cuban Giants, cakewalkers entertained wealthy white audiences in spaces like the Ponce de Leon Hotel, toeing the line between agency and caricature. The question of who performs, for whom, and at what cost is central to these works. These men lived at the intersection of post-emancipation hope and systemic racism. Their efforts helped pave the way for the Negro Leagues, one of the most successful Black-owned enterprises of the 20th century. And yet, the obstacles they faced—economic, social, psychological—still resonate today.

In this work, I offer both homage and interrogation. I pair contemporary portraiture with archival materials, including excerpts from the 1875 Civil Rights Act, to underscore the ongoing struggle for dignity and equity. The Hotelmen is not just a look back—it’s a call forward, asking us to reckon with what has changed and what remains.

(with reference to Gylbert Coker, “The Hotelmen,” exhibition catalog essay, 2022, and Alexa Brantley, CEAM Art History Intern, 2023)

her own things

her own things is a visual conversation between Black women—an intimate reckoning with identity, self-love, and reclamation. The work begins with a question: What parts of ourselves have been taken, and what have we given away? Inspired by bell hooks’ theory of the oppositional gaze and Ntozake Shange’s for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf, this body of work is both personal and political. It stems from my own experience as a young Black woman in a predominantly white art school, struggling to speak my truth in spaces not built for me.

Shange’s words—somebody almost walked off wid alla my stuff—unlocked something in me. Her poem helped me understand that reclaiming my voice, my joy, my rhythm, my “stuff,” was an act of survival. And survival, for Black women, is a rebellious act.

her own things is a conversation—quiet, layered, and ongoing—between Black women about identity, memory, and self-worth.

her own things is a conversation—quiet, layered, and ongoing—between Black women about identity, memory, and self-worth.

Oh, Snap

What happens when we stare back?

When we see you seeing us?

When we see us seeing us?

When I see me seeing me?

Reckoning.

This is the beginning of a story I want re-tell.

My work has always been rooted, conceptually, to the oppositional gaze, a term penned by cultural critic bell hooks. For me, it is the intentional act of changing one’s relative position from spectacle to spectator. It is to snatch back the power of looking and the agency that it presumes.

While studying the history of the Black Arts Movement (the mid-1960s – 1970s), I ran across a plea from its founder, Amiri Baraka (Leroi Jones), in his “imagetext,” In Our Terribleness, a book that united his poetic narrative to photographer Fundi’s (Billy Abernathy) documentary photography. The book is an exploration of the power of the gaze. In it, he speaks of what he considered the state of hypnosis that Black Americans were under. A trancelike state of mind that left us disconnected from our authentic selves both ideologically and aesthetically. The goal of the Black Arts Movement was to revision what it was to be black in spite of historical assumptions, acts, prejudice, and conditioning. To not only to marry the ideological and the aesthetic but to fully align them as one, hence the slogan, “Black is Beautiful” – Black. Is. Beautiful. He insists, though, that he cannot lead African-Americans in the decolonizing state of counter-hypnosis. He urged Black Americans to “try to see your own face when you close your eyes” then “get up and go.”

Knowing that my exhibition would be paired with a musical performance, I dedicated some time to listen to the music in an effort to tie its influence into my body of work. The music of Sybarite5 almost immediately made me think of the word trance. Its sweeping effect lulls you into a space where only they exist. A space ripe with anticipation that binds you to that moment. Then it lets you go. Leaving you to reconsider where you were, or even who you were, in the first place. This is the space wherein the music and my studies came together.

“Oh Snap.” is an exploration of the moment after we are snapped out of hypnosis, the instant when we let go. The immediate confrontation between who we are and what we see staring back at us…ourselves and you.

Shelter-in-Place

Shelter-in-Place reflects on the ways Black women and girls seek safety in spaces that are often layered with risk. The act of sheltering—finding refuge in a place already occupied—mirrors how we navigate the world: mentally, emotionally, socially, spiritually, and physically. Even amid danger, real or perceived, we carve out space for joy, connection, and survival.

Rooted in inherited cultural codes, this work explores the visual and verbal language we’ve developed to move through both marginalized and mainstream spaces. Drawing on the forms of a maze, a funhouse, and a playground, the exhibition examines how these environments disorient, challenge, and nurture us—simultaneously confusing, confronting, and inviting us to play.

Through painting, installation, sound, and signage, I consider how language—spoken, written, and felt—shapes identity and access. Shelter-in-Place is a study in dualities: safety and danger, attraction and repulsion, visibility and erasure. It’s about how we move, communicate, and hold space for one another while making sense of the world around us.