"Angela Fraleigh: Our world swells like dawn, when the sun licks the water" at Inman Gallery

September 12 – October 31, 2020

Exhibition open by appointment: Tues. – Sat., 11 – 6

Inman Gallery is pleased to present two concurrent exhibitions to celebrate the gallery’s 30th anniversary: Our world swells like dawn, when the sun licks the water by Angela Fraleigh, and IN PIECES ON FIRE by Robyn O’Neil. The exhibitions present new bodies of work by each artist.

Opening Saturday, September 12, they will continue by appointment through Saturday, October 31, 2020. In lieu of a public opening, there will be public programs via Zoom scheduled throughout the run of the exhibitions.

Angela Fraleigh’s lush and complex works mine the history of academic and avant-garde painting, and are often created as site specific projects to recontextualize the unique collections of public institutions. Our world swells… consists of five large, immersive canvases from two bodies of work. Three of the paintings were part of Fraleigh’s recent solo exhibition commissioned by the Delaware Art Museum in Wilmington, Delaware. Sound the Deep Waters responded to the institution’s strong holdings of Pre-Raphaelite paintings and American illustration using the lens of historical narrative art to explore contemporary issues of gender and identity.

She describes the exhibition as being “…part of a longtime project that asks, What if the female characters we’ve come to know from art history—the lounging odalisques, the chorus that whispers in the background—present more than a voyeuristic visual feast? What if these characters embody a flickering of female power at work? Can we see these passive characters as subversive and powerful? And if we do, how might it affect women today and of the future?”

These ideas are carried forward in her newest body of work, created on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of a woman’s right to vote. Two of the paintings are on view for the first time. While conducting research for the Delaware Art Museum exhibition, Fraleigh came across several first edition feminist texts from the 18th and 19th centuries with unique marbled endpapers, and some with unexpected provenances. She points to one book in particular as a source of inspiration: a copy of the “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman" by Mary Wollstonecraft, which featured a gift inscription to "Mrs Horace Brock with Dr Henry Biddle's respects and best wishes, January 1915". Mrs. Brock, was the President of the Pennsylvania Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage and Dr. Henry Biddle was a known suffrage supporter.

Fraleigh states, “I love that this gorgeous marbled cover, from a male suffrage supporter to a female anti- suffragist, came to represent something uniquely different to both of them, and that something so benign as a marbled cover could come to be a stand in for a revolutionary subversive text."

In Fraleigh’s two newest paintings figures emerge from a similarly hand- marbled background, but at a massive scale of 5.5 x 7.5 ft. In Take root among the stars, a work whose title references Octavia Butler's novel “Parable of the Sower,” three black women loom large, emerging from the marbleized paper and communing as the mythological goddesses the Fates. In both paintings, Fraleigh presents her women as archetypal, powerful figures who share and hold knowledge. The title of Fraleigh’s second work, With ready eyes, references transcendentalist author Margaret Fuller, whose book “Woman in the 19th Century” is thought to have inspired the women's suffrage movement. In Fraleigh’s composition, we see two female figures listening intently to a third figure reading aloud. Perhaps they are scheming with seditious intent or telling the tale of the hallucinatory feminist utopia that unfolds in the main gallery.

Ghosts in the Sunlight

The Morning News:

The women in this series, where did you find them?

Angela Fraleigh:

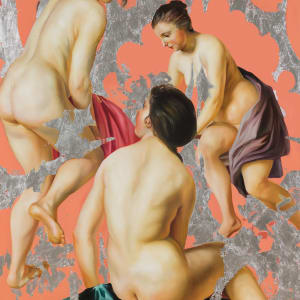

The body of work borrows figures from a variety of painted mythological interpretations by old masters—Diana After the Hunt, The Rape of Europa, and The Allegory of Fertility, among others.

The fraught sensuality of these stories has been compounded, over the years, by their representation. The women in my work are originally from paintings by Baroque and Rococo masters such as Jacob Jordaens, Francois Boucher, Francois Lemoyne. In their work the stories were sifted through the lens of the painter and through the eyes of an era. These were artists whose great themes were pleasure, beauty, and abundance; hints of refusal, fear, or coercion would only spoil the party.

The echoes of these idealized forms still reverberate and lap at the shores of our consciousness, forming the ways we come to understand ourselves and make meaning in the world.

By pulling at the shadows of old-master paintings my work asks the question of what dormant new narratives might be found in the female subjects that inhabit them. What invisible histories lay in wait, or what complexities of power might be unearthed? Is it possible to restore autonomy to these models, to whatever nuances of expression might’ve been contained in their poses? Maybe it can’t be “restored”—they’re long gone—but perhaps something new might be revealed.

TMN:

So how did the work begin to take shape?

AF:

While on sabbatical this past year I began looking at origin stories and thinking about myth. I was reading through Joseph Campbell’s theory of the “monomyth” when I realized there were few female protagonists that fit that particular narrative structure of the hero’s journey. I wondered if there would be a difference—could there be splintered versions of the hero’s journey to encompass the nuances of the female experience?

Then I found Marina Warner and have been greedily consuming everything she’s ever written. Her book From the Beast to the Blonde, in particular, has been fodder for the way I’ve been thinking though this latest body of work. In it she talks about how women’s voices have been silenced throughout the ages. She displayed several propaganda style prints from the Middle Ages to the present warning against the dangers of women gathering and gossiping. Women knew things—they knew how to have abortions, they knew about sexual pleasures; they had medicinal tinctures and so on.

In many ways the Hero’s journey for the female character resides in fairytale. Not the sanitized Disney version, but the erotic and violent wonder tales told the world over by “old biddies,” grandmothers and nurses. These are stories that had been passed down by generations of society’s voiceless women. These stories taken out of context and devoid of their bite read as entertainment, but in their day they were the whispers of progress: At times cautionary tales, in other instances emotional dramas meant to inspire rights and privileges outside normal social codes of the day, all moving toward broader terms of freedom for the narrator and her coterie.

TMN:

Did these appeal to you on a painting level?

AF:

I liked thinking about these gatherings, whether it be the birthing bed, the bakery, or in the salons of the aristocrats, as subversive meeting places where women could network. And that sharing stories alone might be so powerful as to instigate change.

Many of the paintings that I chose to re-envision are taken from the Rococo era, an era often swept under the rug of art history for its femininity and frivolity. This was a time when women were key players in the creation of culture. Women like Madame Pompadour were the primary patrons of many of the artists associated with that time such as Boucher and Fragonard. Much like the stories being told of that time and their role in creating more opportunities of freedom for women, this body of work questions those complexities of power. How we might use what we have to get what we want.

TMN:

So much focus here is on the body—sensuality, complexity, gradation. What compels you most to paint these days?

AF:

What is the famous de Kooning line? Flesh is the reason oil paint was invented?

For me flesh is the perfect subject to perform all the things I love most about painting. Oil paint is so versatile—it can be pushed to so many extremes. Juicy slabs, silky wisps, transparent floods of color. There is topography to painting, one you have to be fully present to see and understand. You can’t really get it from reproduction, and in this digital age I take great solace in that. The paintings I love the most are generous in this way. They have a scaffolding, a built effect that beckons an optical engagement, asking one to read not only the surface, what it is and what it means, but also to read the internal structure, eyeing from the tippy-top membrane down deep into the weave of the canvas.

TMN:

When did the addition of the metal leaf occur to you? Was the idea more inspired or calculated?

AF:

The use of gold leaf is new in my work but in my mind functions similarly to the pours of glossy oil paint you might see in some of the other works, both formally and conceptually.

The process of painting most of my images alternates between control and chance. I’ll lay out the figurative composition in a traditional upright manner, but then lay the canvas flat and pour cupfuls of oil paint and synthetic resin. This creates more of a collaborative process, as it inevitably invites indiscriminate painterly moments that I don’t intentionally create or control.

Conceptually this process allows the paint to function as a protagonist in the narrative. The physicality of the paint both cankers and covers the story, obscuring individuals and becoming a carrier of meaning. Through the examination of power dynamics of social constructs, like gender and class, the paintings often expose the fissures that occur when the ideals from one point in history are translated into another.

TMN:

But on a technical level, before meaning’s introduced, how does it work?

AF:

For a while I had been wanting to incorporate a visual effect that would read as more embedded in the paint, something seductive that would also read as decay, less visceral yet opaque.

I began tie-dying the canvas before painting on it to see if that would yield anything. I also started painting on printed textile and recreating tapestries as a ground for the figural elements. Nothing really came together, but all of that eventually led me to textile design as an abstract element—and thinking about the first female textile designers.

One that popped up in my preliminary searches was Candace Wheeler. She was one of the first women to be paid for her work with Tiffany. She created an all-woman design firm, Associated Artists, and fought hard for the economic freedom for women in the early 1900s. The gold-leaf abstractions in all of the new paintings are a pattern taken from one of her designs.

Anyway, I was playing with painting in the textile design but it wasn’t giving me the same charge, so I tried the gold leaf and found it served my needs on several levels. It’s alluring—you want to look at it, but when light hits it, it pushes back out at you. It was a physical way to mimic the experience of thinking you see one thing, but in fact see another.

TMN:

You put a lot of care and lyricism into your titles.

AF:

I like how a title can sit beside an image, not illustrating it or describing it, but holding its own, creating something new—something entirely different, that perhaps the painting alone doesn’t do. Titles can puncture or punctuate; they can undermine assumptions or complicate the image. They might make the reading feel broader or point to something nuanced without being overbearing. I’m really interested in that moment between the text and the image, that area between that reads as a sigh, a shudder, or a pause.

The titles I choose are often fragments from larger texts—half a line from a poem or a scrap of dialogue. These found snippets echo the fragmentary nature of the images themselves. I collect these strings of words, and when a painting is finished I hold them up one by one, hoping to find a match, a combination that yields something greater than the sum of its parts.

Lost in the Light: Vanderbilt Mansion

Contact:

Frank Futral, Curator,

The Vanderbilt Mansion

…

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

October 9th, 2015

Angela Fraleigh

Lost in the Light

The Vanderbilt Mansion, Hyde Park, NY

October 9th, 2015 - May 25, 2016

HYDE PARK, N.Y.—The Vanderbilt Mansion is pleased to present Angela Fraleigh: Lost in the Light October 9, 2015–May 25, 2016. Fraleigh is widely known for lush, complex paintings that examine and explore power dynamics. Fraleigh’s work often tugs at the shadows of art history in search of invisible histories and dormant new narratives that might restore agency to the women that inhabit them. Mounted in the historic rooms will be 10 intimate “portraits” of female heads from behind, as well as one large 5x8ft painting in the main entry.

Much about the cast of characters that inhabited the Vanderbilt mansion remains a mystery, but none more so than the women of the era. We can find logs of men’s lives and men’s matters; men mattered. But even the female sex of the upper class were regarded with little account unless tabloid worthy. And although various members of the Vanderbilt family plastered the penny pages, Fred and Louise Vanderbilt shunned the spotlight. Perhaps that’s why we know so little about them.

There is very little evidential account of Louise Vanderbilt, and the upper-class guests that frequented the residence, as well as the servants, maids and cooks that scuttled in the shadows, behind closed doors. Much about the women who lived on the estate during this period remains elusive, as do the women in Fraleigh’s paintings.

Installed in the guest bedrooms of the Vanderbilt mansion are 10 small portraits of female heads seen from behind, the features of their face removed from view. The compositions are pared back to four elements: the limited background and the subject’s hair, skin and clothing.

In many of the back portraits—we cannot tell whether the subject is a maid or a member of the elite, or even guess what she is doing. She is enigmatic, contemplative, absorbed in some task, or dashing out of the room to continue with the responsibilities of the day. The silent figure is closed off from us and removed, enlivening our interest in the figure’s interior world. She is confessing a gulf of human experience into and out of the painting, a space beyond our reach, beyond our vision.

The tight framing of the work gives the perception of closeness to the viewer, as perhaps expected of a traditional portrait. Yet the portraits are without overt symbolic detail: no clear reference is made to class, interests or hobbies. There is a democratizing quality to this approach, one that makes all the women equal regardless of their very un-equal station in life. Yet, this highlights the lack of autonomy women had during this period; whether it be equal wages for equal work, property and custody rights or the right to vote, women were second-class citizens regardless of their economic standing.

The paintings are fixed within this state, communicating an atmosphere or essence, but firmly removed from storytelling. The portraits are mute. There is a silent refusal to expound a narrative; an emphasis on stillness, and the passage of time. These images are somewhat impenetrable and isolated, arousing longing for the stories that peopled this home, but offering only a whisper.

Accompanying the exhibition will be a unique book collaboration between Fraleigh and writer Jen Werner. The book is an attempt to give a voice to the women that lived, visited, and worked in the Vanderbilt's country house at Hyde Park. Based on oral histories, primary and secondary historical documents, and the muse of invention, this book is a tribute to the physical and psychological aspects of female life during the Gilded Age. Included in the book are partially invented stories meant to invoke not only the spirit of Louise Vanderbilt and the women who surrounded her, but also the necessary role that women played in this grand American history.

# # #

Shadows Searching for Light

Edward Hopper House Museum & Study Center is pleased to announce Shadows Searching for Light, a new site-specific installation by Angela Fraleigh inspired by the paintings of Edward Hopper (1882-1867) and his relationship with his wife, Josephine

(Jo) Nivison Hopper (1883-1968). The installation is a continuation of Fraleigh’s most recent body of work, paintings which reimagine and recontextualize marginalized female figures by freeing them from their previous roles in art history.

Exploring the psychological space within Edward Hopper’s paintings, and the dynamics of the Hoppers’ two-artist marriage, Fraleigh focuses on the women who inhabit Hopper’s artwork – dramatic figures almost always modeled after Jo Nivison Hopper herself. In a vibrant transformation of the main gallery space at the Edward Hopper House, Fraleigh’s wall coverings are inspired by Jo’s bold palette and vigorous, animated brushwork. They provide a fitting backdrop for paintings that reflect Jo Hopper’s often isolated persona within the context of her relationship with her reclusive husband.

At the time of her marriage to Edward Hopper in 1924, Jo Nivison was a respected artist in her own right exhibiting in New York City galleries with American modernist masters Stuart Davis, Maurice Prendergast, and Man Ray, among others. Charles Burchfield’s first New York exhibition was a two-artist show with Jo; her diary refers to “Burchfield’s show on the right side wall and Jo Hopper’s watercolors on the left and in the window.” When the Hoppers began courting in the summer of 1923 Edward had been struggling to sell his paintings – getting by on the income from the commercial illustration work he despised – until, with Jo’s assistance, he sold his first painting in a decade to the Brooklyn Museum. Jo had been invited to show her work in a prestigious exhibition there and convinced the curators to include Edward’s new work as well. The sale represented a pivotal turning point in Hopper’s career and after their marriage, as interest in his work burgeoned, Jo’s output, and the enthusiasm for her work, waned.

As curator Elizabeth Colleary noted, “for more than forty years Jo devoted herself to helping Hopper flourish in the art world while their personal relationship suffered. She was always the stalwart supporter of her husband – serving as his model and muse, and meticulously documenting his artistic output – while she struggled to maintain vestiges of her own creative life. Her husband would denigrate her efforts but she nonetheless plodded on, enjoying the many hours the artists spent painting side by side and producing some of her best, though largely unseen, work. Jo would be heartened by Fraleigh’s efforts to position her so prominently as an artist in her own right, and within her husband’s creative process – recognition that is long overdue.”

In preparation for the installation at Edward Hopper House, Fraleigh received permission to photograph source material for the paintings in the space the Hoppers lived and worked, at 3 Washington Square North, now owned by New York University. She states “It’s a somewhat sentimental or romantic gesture, photographing a contemporary model in the Hopper home, with the same light Hopper would have painted from, positioning the figure in the same place Jo would have posed--- the model role-playing Jo, who was role-playing Hopper’s “women”… but in the paintings that come from this process I’m hoping to draw out the lost threads of this particular history and connect it to contemporary concerns of agency, identity, access and power. Jo’s influence is blaring from the walls, seeping into the space, while the expressionless figures, lost forever in thought, meditate on what could have been for Jo and what could be for them.

The Raving Ones

Sean Horton (Presents) is pleased to announce a special project by American painter Angela Fraleigh for the VIP Lounge of Untitled Art, Miami Beach 2022. The Raving Ones is a 28 foot painting installation presenting three major (78 x 57 inch) paintings on hand-drawn wallpaper made especially for the fair.

Artist Angela Fraleigh has spent her career exploring narrative art’s hierarchical patterns. Keenly observing how images and roles from Western art history intersect with contemporary representation and attitudes, Fraleigh uncovers why certain tropes remain relevant, who they benefit, and how. Over the last decade, she has worked with institutions to create several site-specific solo exhibitions that reveal alternative accounts in their permanent collections. In rearranging the images of the past, the artist transforms how we see ourselves in the present.

In this new series Fraleigh draws parallels between art production and spellcraft, harnessing the magic of making the invisible, visible. Ecstatic Maenads gather amongst a frenzied tangle of medicinal herbs and serpents to raucously summon the powers of mythical female figures such as: Artemis, Hecate and Medusa to aid in casting a spell.

The maenad serves as a symbolic abandonment of the confining roles and identities of femininity and as an embrace of the pleasure seeking erratic, rebellious, unconcerned-with-popular-opinion kind of figure. In ancient sources, their transcendence gives them unparalleled strength and courage as well as a disregard for earthly consequences. Followers of Dionysus, referred to as the “The Raving Ones”, were feared because of their wildness, and they became a considerable source of fright for those who would seek to contain them.

Each painting serves as a kind of spell — one that disrupts, re-imagines, and re-signifies the female characters from familiar tales so as to challenge our perceptions of the past and experience a different future.

The links between the “witch” and systemic power structures such as capitalism, organized religion, and the patriarchy are profound and painfully relevant today as it relates to female power, bodily autonomy, and persecution. In her ground-breaking book Caliban and the Witch, Silvia Federici makes the important claim that the medieval witch-hunt across Europe was a necessary precondition for the emergence of flourishing capitalism. Women’s speech, movement, and social relationships were tightly controlled with the help of witch hunts and accusations of witchcraft on poor, peasant women, were in part an effort to dispossess them of the land they lived on. The witch-hunt was about controlling women’s bodies to repopulate a workforce for the wealthy.

In this moment of violent, institutional attack on bodily autonomy, the maenad responds with wild, joyful, reckless love and fierce, frenzied, protective anger–summoning the power to upend damaging societal structures.

Threaded with moonlight

Angela Fraleigh’s paintings retrieve women from the margins of history, offering alternative, empowering visual narratives. Plucking figures from the art-historical canon and placing them in new, dreamlike compositions, she creates space for female agency and subversion.

In Threaded with moonlight, a new body of work created for this exhibition, Fraleigh explores textile-making as an act of power. Her paintings depict women holding distaffs plump with unspun fiber, manipulating thread into cloth and lace, and wielding shears—mundane tasks that could potentially invoke potent forces. In folk religions across Europe, goddesses spin, measure, and cut thread to determine the span of a human life, while cultures worldwide draw parallels between female deities making textiles, the creation of the universe, and destiny.

Fraleigh also considers portrayals of witches, spinners, and weavers in mythology and fairy tales, and their access to temporal or supernatural power through textiles.

Drawing inspiration from the Museum’s rich holdings, Fraleigh situates her female protagonists amidst textile motifs traditionally used to invite abundance, blessings, and protection. Her monumental paintings envision a lush landscape ripe with magical potential, while the silk drape behind them riffs on the tree of life, an ancient symbol of fecundity. Fraleigh positions these varied motifs as not only a complex, subversive language that might covertly express dangerous dreams and desires, but also as talismans, protective charms that could imbue everyday textiles with intention and power. The exhibition also presents select textiles from the Museum collection that inspired Fraleigh’s work, inviting a chorus of makers’ voices into the gallery.

Informed by folklore, diverse spiritual practices, and textile traditions from across four continents and sixteen centuries, Threaded with moonlight disrupts the docile femininity usually associated with textile work. Fraleigh’s women seize the everyday rhythms of spinning, stitching, and weaving as ritual and incantation—transforming their work into a space for communication, harnessing power, and forging new possibilities

The female figures in this trio of paintings evoke the Fates or Norns, the goddesses who spin to determine destiny in Greek and Norse tradition. Yet these figures might also be human women, engaged in the everyday work of textile production—labor that, with its divine associations, offered opportunity to harness supernatural power.

Fraleigh creates an environment for these figures that brims with magical possibilities, employing varied imagery from the Museum’s textile collection. She selected textile motifs based on their traditional meanings and invocations: for instance, flowers, woven and embroidered worldwide to invite fertility and abundance; and stars, a symbol of celestial harmony and the passage of time. Other textile designs used here include labyrinthine patterns intended to confuse evil spirits, and geometric motifs used to offer strength and protection.

Building on the layers of meaning embedded in her work, Fraleigh also incorporated moonwater, ground crystals, and paint made from gemstones that hold supernatural significance in various traditions.

Women Reading Watercolor series

The women reading series examines and explores images throughout history of various women in the private act of reading. At first glance the figures are passive, but, reading is an inherently active pursuit. They may be time traveling, embodying a different race, gender, economic class, a different species, a different planet. It might be pleasurable, horrifying, edifying... reading opens up possibility, shows potential, allows for empathy and compassion and ignites the imagination.

A whole world is happening within them while they are being objectified. That points to the heart of my ongoing project.... which examines how we understand images, what lens we look through when we encounter images, and the gulf of space between what we think we know and what we could know. It explores the way we are forever compressing all the complexities of the human experience and the power dynamics inherent within that unintentional act.

Women were actively barred for centuries from becoming literate out of fear of what they might learn/ do with that knowledge. The quakes of that remain today, as Nearly 2/3 of the worlds illiterate adults are women.