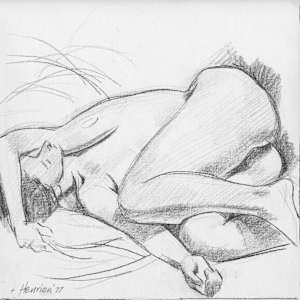

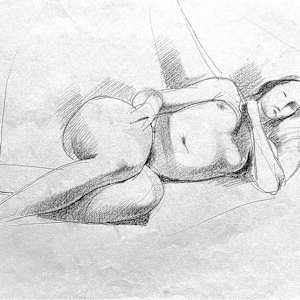

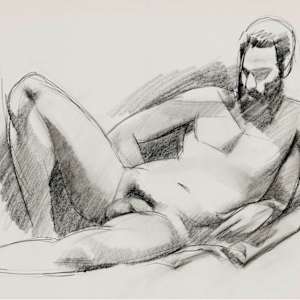

A. Life Drawings

The softer side of his nature was evidenced in his exquisitely drafted life drawings of the human figure.

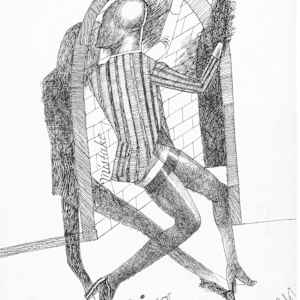

B. Satirical Works

"Ed Henrion’s Razor Line Cuts to the Core of our Common Depravity" An essay by Ed McCormack, one of the original contributing editors of Andy Warhol's Interview and a former feature editor and columnist for Rolling Stone. (2011)...

" If most artists are said to have a muse, it might be assumed that the satirical draftsman Ed Henrion has an imp that hops out of an ink bottle like Ko-Ko the Clown in those vintage black and white animated cartoons of the 1920s.In captivity for over half a century, that demonic imp has finally emerged with a vengeance in the present volume, at the persistent urging –– one might even call it nudging –– of Henrion’s wife, the well-known fiber artist Marilyn Henrion. While Ed masqueraded for many years as a mild-mannered high school art teacher at Erasmus High School in Brooklyn, the couple were steeped in the lively downtown art and literary scene of the ‘60s and ‘70s. They held regular salons in their Greenwich Village apartment where Allen Ginsberg, Philip Lamantia, Ray Bremser, and other Beat Generation luminaries read poetry, avant gardists such as Jackson Maclow performed, and their social set included visual artists such as Joseph Cornell, Tom Wesselman, and Claus Oldenburg, in whose happenings Marilyn performed. But aside from contributing a few freelance editorial illustrations to small publications such as Human Events and Libertarian Review, Ed (apparently a retiring man long before he retired) wanted no part of the art business per se. This despite having been a regular, along with de Kooning, Rothko, Motherwell, and other big guns of the New York School, at the legendary Artists Club on 8th Street in the 1950s, and having, for a time, painted large canvases in the manner of a latter-day Matisse (whom he has come to resemble, with his owlish specs and white beard, in recent years). It would seem that the distance Ed Henrion has kept from the grubby, hustling aspects of the art scene has served his graphic vision well, giving him the freedom to skewer aspects of the cultural establishment that might be off- limits to a more professionally ambitious satirist. Not even that once vaunted arbiter of Hip, The Village Voice, was safe from his acid-etched pen-line, judging from one scathing drawing of a flamboyantly foppish critic / commentator in high-heeled pumps posturing at his typewriter, while multi-culti artsy-fartsy wannabes salivate at a window bearing the paper’s familiar logo like Oliver Twist ogling the porridge. And doesn’t that little cutie in the diaper, sucking on a pacifier and clutching a stuffed teddy bear in another drawing, bear a suspicious resemblance to Picasso? Other personal acquaintances and / or cultural icons such as Allen Ginsberg or Jascha Heifetz may occasionally put in cameo appearances –– rarely in flattering roles. (Could that dandyish dude studying the funky folk singers in Washington Square as if they were bedbugs under a microscope be none other than the natty New Journalist Tom Wolfe?) But it’s never necessary to recognize them in order to appreciate these drawings for their own wicked virtues. For, even when likenesses or details suggest a particular time period, these pictures are never merely topically obvious in the manner of a political cartoon. Rather, they attack the larger, more timeless and universal themes of human nature in a more elusive, enigmatic way that puts Henrion on a par, for both his breadth of vision and his draftsmanly abilities, with better-known graphic satirists such as Gerald Scarf, Ralph Steadman and Tomi Ungerer. For surely Henrion’s figurative distortions are as wildly inventive and over the top as those of the two British artists, Scarf and Steadman (if more intricately filled with linear swirls and crosshatching in a style suggesting Edward Gorey on acid), and his delight in depicting kinky erotic fetishes equals that of the Frenchman Ungerer. When Henrion ventures into color (mostly in what looks to be watercolor, gouache, colored pencil, or pastel, combined with that always incisive ink or graphite line), hints of the fine painter he once was are clearly evident. But as with George Grosz (the master to whom he, like all the other terrific draftsman mentioned in this appreciation, is most beholden), it is in a razor-sharp line, cutting to the core of our common depravity, that Ed Henrion finds his true métier. *

" If most artists are said to have a muse, it might be assumed that the satirical draftsman Ed Henrion has an imp that hops out of an ink bottle like Ko-Ko the Clown in those vintage black and white animated cartoons of the 1920s.In captivity for over half a century, that demonic imp has finally emerged with a vengeance in the present volume, at the persistent urging –– one might even call it nudging –– of Henrion’s wife, the well-known fiber artist Marilyn Henrion. While Ed masqueraded for many years as a mild-mannered high school art teacher at Erasmus High School in Brooklyn, the couple were steeped in the lively downtown art and literary scene of the ‘60s and ‘70s. They held regular salons in their Greenwich Village apartment where Allen Ginsberg, Philip Lamantia, Ray Bremser, and other Beat Generation luminaries read poetry, avant gardists such as Jackson Maclow performed, and their social set included visual artists such as Joseph Cornell, Tom Wesselman, and Claus Oldenburg, in whose happenings Marilyn performed. But aside from contributing a few freelance editorial illustrations to small publications such as Human Events and Libertarian Review, Ed (apparently a retiring man long before he retired) wanted no part of the art business per se. This despite having been a regular, along with de Kooning, Rothko, Motherwell, and other big guns of the New York School, at the legendary Artists Club on 8th Street in the 1950s, and having, for a time, painted large canvases in the manner of a latter-day Matisse (whom he has come to resemble, with his owlish specs and white beard, in recent years). It would seem that the distance Ed Henrion has kept from the grubby, hustling aspects of the art scene has served his graphic vision well, giving him the freedom to skewer aspects of the cultural establishment that might be off- limits to a more professionally ambitious satirist. Not even that once vaunted arbiter of Hip, The Village Voice, was safe from his acid-etched pen-line, judging from one scathing drawing of a flamboyantly foppish critic / commentator in high-heeled pumps posturing at his typewriter, while multi-culti artsy-fartsy wannabes salivate at a window bearing the paper’s familiar logo like Oliver Twist ogling the porridge. And doesn’t that little cutie in the diaper, sucking on a pacifier and clutching a stuffed teddy bear in another drawing, bear a suspicious resemblance to Picasso? Other personal acquaintances and / or cultural icons such as Allen Ginsberg or Jascha Heifetz may occasionally put in cameo appearances –– rarely in flattering roles. (Could that dandyish dude studying the funky folk singers in Washington Square as if they were bedbugs under a microscope be none other than the natty New Journalist Tom Wolfe?) But it’s never necessary to recognize them in order to appreciate these drawings for their own wicked virtues. For, even when likenesses or details suggest a particular time period, these pictures are never merely topically obvious in the manner of a political cartoon. Rather, they attack the larger, more timeless and universal themes of human nature in a more elusive, enigmatic way that puts Henrion on a par, for both his breadth of vision and his draftsmanly abilities, with better-known graphic satirists such as Gerald Scarf, Ralph Steadman and Tomi Ungerer. For surely Henrion’s figurative distortions are as wildly inventive and over the top as those of the two British artists, Scarf and Steadman (if more intricately filled with linear swirls and crosshatching in a style suggesting Edward Gorey on acid), and his delight in depicting kinky erotic fetishes equals that of the Frenchman Ungerer. When Henrion ventures into color (mostly in what looks to be watercolor, gouache, colored pencil, or pastel, combined with that always incisive ink or graphite line), hints of the fine painter he once was are clearly evident. But as with George Grosz (the master to whom he, like all the other terrific draftsman mentioned in this appreciation, is most beholden), it is in a razor-sharp line, cutting to the core of our common depravity, that Ed Henrion finds his true métier. *

C. Paintings

A limited number the artist’s original paintings have survived his practice of painting over earlier canvases, testifying to his humility and unconcern about thoughts of “preciousness”. In addition to a few of the original works, archival prints offer a way to preserve the images of those that did manage to survive over the years, from the earliest canvases created in Chicago in the late 1940’s to the late 1990’s when he abandoned the paintbrush.

D. Publications

Edward Henrion gave up making art in the early '90's and became an avid chess player and science enthusiast. In 2011, he finally allowed his wife to introduce his extraordinary body of work to the public with the publication of two books of his satirical drawings which had never been exhibited or published, "Sweet & Lovely" and "Top Hat". A final book, "Mickey Rat" was published posthumously in 2017. All are now available on amazon.com.