Another grassland dabbler, the Wilson’s Phalarope turns the tables on ‘gender roles.’ Females are more richly colored than males, peachy and gray, and court and defend male mates—several per season. Males do most of the work of raising the young and even building the nest. Their call is a short, nasal “thrip! Thrip!”

While flocking together on migration, they spin round and round in the nutrient-rich waters of salty lakes, creating whirlpools that stir up invertebrates that will fuel their migration to South America. Hundreds of them can be seen spinning and foraging together. In fact, they usually eat so much that they double their body weight. Sometimes they get so fat that they cannot even fly!

Diet is mainly small aquatic invertebrates such as midges and shrimp. Aside from spinning whirlpools, techniques include chasing and pecking prey from the surface of mud or water, standing still and stabbing at passing flies, and probing inside mud.

Though their numbers are stable at this time, they still depend on wetland habitat, water quality, and surface water availability. On migration, they stage in huge numbers at hypersaline lakes such as Mono Lake and the Salton Sea. Because so many birds congregate, changes to these areas including water diversion and reclamation could have serious repercussions.

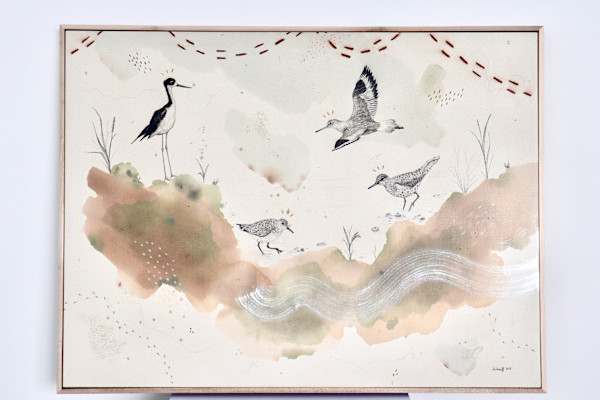

Original mixed media on raw stretched canvas with maple float frame. Alternative hardwood frames available upon request.

Sources: All About Birds and Audubon Society

- Subject Matter: shorebirds/waterfowl

- Collections: Shorebirds & Waterfowl of the Prairie