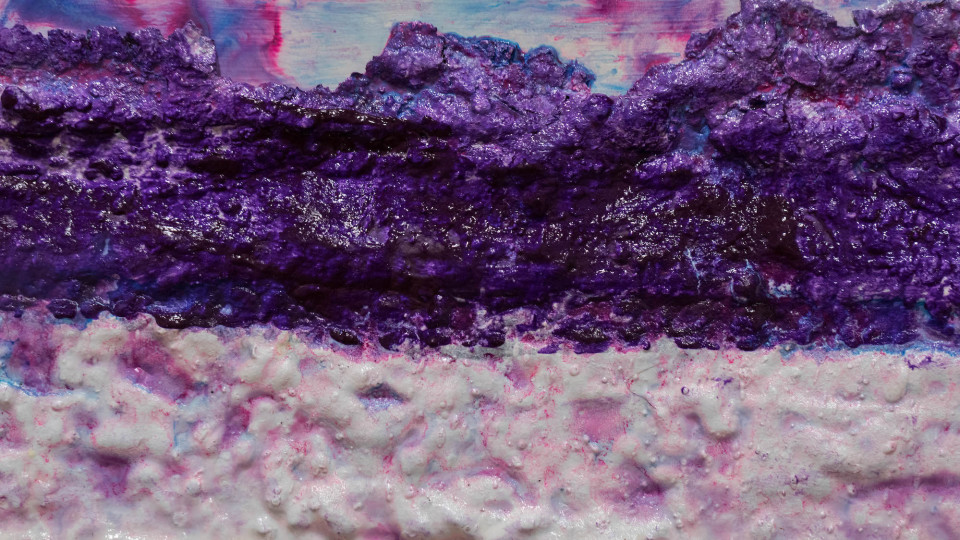

Image: Jacqueline Ehlis's Laffy Taffy (detail), photographed by Mikayla Whitmore

Barrick volunteer and freelance journalist Michael Freborg returns to our blog with his thoughts about a fundamental question: what is art?

Working as a Barrick volunteer, I have seen a lot of artwork displayed in the galleries over the years, but the pieces in the Plural exhibition always stood out to me. The 2018 show featured works from the Museum’s permanent collection, and I fondly remember all the different shapes, sizes, colors, and mediums on display. The first time I walked through the exhibition, I was impressed by Daniel Samaniego’s enormous (10 x 15 ft.) three-dimensional installation. The eight jagged pieces jutting out of the wall like glass shards seemed as if they were flying toward me. And the tormented, macabre faces made out of graphite, conté, and ink on mounted paper, were a striking sight. Its drab grey and black colors gave it a morbid feel, but I felt that was the artist’s intent. I was also amazed by Noelle Garcia’s intricate Native American beadwork resting neatly on a small table. The tiny glass bead chips, cigarettes, and breakfast cereal pieces paled in comparison to Samaniego’s display, but had no less impact on me.

Some of the art I found aesthetically appealing, like artist Jacqueline Ehlis’s Laffy Taffy. The vibrantly colored swaths of paint, all vertically aligned on the wall, reminded me of the frosted cakes I often see at the grocery store. Other art was intentionally difficult to look at, but, at the same time, hard to keep my eyes from. One such piece was artist Julie Oppermann’s acrylic on canvas painting TH1223, with its overlapping lines and shapes. Using her background in neuroscience and color theory, she had made an artwork that caused a dizzying effect when viewed from different angles. I was also impressed by the rhythmic painting of London-born artist Tom Bavington, where he converted a song into vertical bars. And my favorite display in Plural was the mannequin dressed in a makeshift mermaid outfit made by artist Aaron Sheppard. The silver, turquoise, and pink cloth costume added character to the exhibition, in my opinion.

The works came in all different forms and the stories behind them were diverse, but they shared one thing in common. They were all considered pieces of art. Some of these works moved me in different ways. I even wrote about them in my blog posts. But I never stopped to actually ponder what art is. And even more so, how would I explain it to someone who has never seen or experienced it?

Last year, A Drawing a Day curator Emmanuel Muñoz conducted interviews with eleven artists who participated in the online A Drawing a Day project. He asked this hypothetical question of them: “If an alien race were to come to Earth today, how would you explain to them what art is? In other words, what would you show the aliens or do or say to help them understand the concept of art?”

Coming from different disciplines and artistic styles and skill levels, the artists gave candid, spontaneous answers, suggesting a variety of teaching strategies that could help aliens to learn about art. Virginia-based artist Marianne Campbell, who has a background in Children’s Literature, offers a unique perspective. As an early childhood teacher, she understands the benefits of hands-on learning. Staying at home during the pandemic gave her more free time to make artwork with her then-2 ½ year-old daughter. Campbell uses materials she enjoyed as a child and teenager. Sometimes she lets her daughter make marks over her work. It is a way to observe how her daughter experiences childhood and also allows Campbell to relive the joy she experienced while making art during her own youth.

Regarding the aliens, she says she would show them her art class. “When it comes to art, it’s really important to let kids just be free with materials,” she says. “As free as possible. I just find that really fascinating to see what they do with materials. And I think that could give aliens an interesting perspective.”

Florida-based artist Sue Havens has a similar idea - show the aliens the different mediums they could use, and let them explore the possibilities. “Like whatever you have, you can make incredible things. Even if it’s like one graphite pencil,” she says. “It’s not really what you have. You can make something out of anything.” The frazzle-haired self-portraits that Havens submitted to the A Drawing a Day project depicted the anxiety and uncertainty she was feeling during the lockdown, but those sketches were not her typical work. She normally creates semi-abstract paintings, murals, and ceramic vessels. Her primary focus is, in her own words, “an ongoing interest in flatness, dimensionality, and pattern in painting and sculpture." Earlier this year, she lectured at the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts, which ironically was named Close Encounters, after Close Encounters of the Third Kind, a 1977 film about first contact with alien visitors. For the convention, she put together a panel of unconventional clay sculptors to engage in a “national-like conversation,” as she calls it. To explain her reasoning, she recalled a scene from Close Encounters where the character Roy Neary, played by Richard Dreyfuss, builds a model of a volcano he can’t seem to get out of his head:

"In the movie, there’s a guy who is frantically trying to create something out of a pile of dirt. Like all the materials are there and he doesn’t know what he’s doing, but he’s trying to get after an idea. And that was sort of the theme of our talk. We’re not ceramics people in the traditional way, but we are people who happen to incorporate clay to get at some other ideas."

A lot of artists of varying skill levels submitted their works to the A Drawing a Day project and later to the exhibition. Non-professional artists of all ages and backgrounds, including young children, had their artwork displayed beside those of professional artists. One thing they had in common was an idea that they wanted to share, so they used materials to bring those ideas to life. Perhaps one lesson that aliens could learn from A Drawing a Day is that you don’t have to be a professional artist to create art. Anyone can do it. All you need is an idea, some materials to work with, and the will to transform your vision into reality. Of course, sometimes a little inspiration is needed to ignite that creative spark.

Assuming the off-world visitors have time traveling capability, artist Jeff Musser, who currently lives in Sacramento, suggests bringing them to an event he attended a few years ago that had a profound impact on him. “I would take them back to L.A. 2017 to see Kerry James Marshall: Mastry at MOCA,” he says. “You can give them the entire history of art, at least from the Western perspective, a certain Western perspective, in that show.” Marshall’s work, which highlights the lack of black representation throughout art history, has inspired many artists, but it was this one event that gave Musser the push to start work on a project he had been thinking about for nearly six years, his White History Month series. Like Marshall, Musser examines issues of race. His large-scale paintings and collages allow him to explore his identity as a white man, the history of whiteness, and to ask the question, “What does it mean to be white?” His art is meant to encourage viewers to look inward, to ask difficult questions about themselves, and to promote dialogue about difficult topics.

If the aliens were as inspired by Marshall as Musser has been - if they saw Marshall’s artwork, and heard his words, maybe they, too, would pick up some materials and create art that would explore racial issues on their own planet. And if they did make it to Mastry, Musser has some advice. “This might potentially be the best of us,” he says to tell them. “So, look at this. And try to give us the benefit of the doubt.”

Boston-based artist Georgina Lewis would take a rather unconventional approach to teaching the aliens. “I would want to gently smack them,” she says. “Not in a hurtful way at all, but in a way that transmits an action to a feeling.” Lewis believes there is something special that occurs when viewing artwork firsthand. Something she refers to as a eureka moment. There is a connection that takes place when the idea or message that the artist is trying to convey through their artwork invokes an emotional response from the observer. This is more likely to occur, she suggests, when the viewer is physically standing in front of the art instead of seeing a picture of it online, for example. “Art can make you think, or it can make you feel, and sometimes it can be instructive,” she says. “Because there’s something about a transmission from one person to the other. And I don’t know if it’s one person to the other, but as a viewer or consumer of art, there’s something that hopefully happens.” After thinking about her answer some more, she proposes a kinder alternative. She hopes that she would have something “marvelous at hand” to share with the aliens. Something to create that eureka moment.

But these feelings aren’t just experienced by the viewers. The creators of the art can feel them too. Las Vegas visual and performing artist Heidi Rider believes there is a certain playfulness in making art that alters the emotions of the artists. “I feel like out of all the creatures on the planet, I think we’re the only ones who make art just for pleasure,” she says. “You know, like birds make these beautiful woven nests, but it’s either to attract a mate or like it’s functional. Right?”

Not all feelings are positive ones, however. Over the course of the pandemic, Rider and many others suffered through a series of emotions, including fear and helplessness. Her face-painting, which she posted on Instagram, gave her an outlet to process her feelings and “wash it off and send it down the drain,” she says. It is a way, as she puts it, to keep sane. Moreso, viewers of her emotion faces took to social media to express how deeply touched they were by them. Whether it be firsthand through their own eyes or through Instagram, the ideas that Rider conveyed through her art have resonated with people. And that is how that special connection, that transmission, that Lewis talks about, takes place. One lesson the aliens could learn from this is that art can be used for artists to explore and work through their emotions. And through their artwork, those feelings can be transferred to the viewers. Rider hopes the aliens would have telepathic abilities so they could feel what others are feeling when they look at art. “If they could feel that, then they would understand it,” she says.

Now if the aliens are going to be taught as students in an academic setting, UNLV architecture student Daniel Magaña might be just the one to do it. He suggests keeping it simple, starting with the basics and expanding to other disciplines. “Like if I had to teach aliens about something, it would be shapes. Cause there’s so many more things you can teach them with that,” he says. “Just branch out . . . you can teach them about science. And you can show them art in every little thing. That’s like the poetic thing about it. There’s art in everything.” One of the shapes Magaña would teach them about is the hexagon, which, he says, is superior because it is structurally the strongest and can be infinitely tiled. Hexagons, along with crosses, he would relate to the geometric aspects of Francesco Borromini’s (1599-1667) architecture. The Italian architect was one of the leading figures of the Roman Baroque style. He designed the Church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane in Rome, in which, for its lower interior walls, he used the types of hexagons and cross shapes Magaña talks about.

From there, Magaña would show how these shapes relate to things like plants and human anatomy. “If you want to be a good art teacher,” he says, “you have to teach it simple. I feel like teaching shapes would be the most fundamental thing.”

Elementary art teacher Christel Polkowski, a native of Las Vegas and a UNLV alumna, would rely on technology to teach aliens about art. She recalls a scene in the 1997 film The Fifth Element where the character Leeloo, played by Milla Jovovich, is watching a slideshow that helps her to learn about human history. “There’s not like one object or one thing that I feel like could convey all of that,” she says. “So, somehow like in my mind that’s what it would have to be.” Like many instructors, Polkowski has had to adjust to online teaching methods over the course of the pandemic. As she suggests, a simple documentary might be a good way to introduce aliens to art.

However, sometimes students learn more from the outside world than in a classroom, and Las Vegas-based multidisciplinary artist Brent Holmes recommends doing just that. Holmes would take the extra-terrestrials on a field trip to the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Texas, and show them the room where Mark Rothko’s painted black panels are displayed. “What I want you to do is I want you to sit and stare at that black,” he says he would tell them. “And you tell me when you see your first hint of blue. And you tell me when you see your first hint of red. And you tell me what that feels like inside of you when you see it. When you spend enough time with it.” He admits the paintings may not be the apex of art, but it would give him a jumping-off point to begin explaining the concept to a group of beings who were new to it. Holmes is drawn to sprawling desert landscapes, with their rolling mesas and lively inhabitants. He is interested in how these enchanting but hostile environments affect the human body and mind. He calls himself a “desert heart,” which, in his words, is a person whose “heart is vast, and hot, and maybe a little dangerous.” The desert, he says, affects his capacity to feel, and to love, and to understand. He believes that he and other artists have an obligation to take the sublime and make it into something new. These empty spaces “bring out resonant truths that you can’t find elsewhere,” he puts it. “And why I was attracted to art was that it is a form of self-soothing. It’s therapeutic . . . All you need is a pencil and a piece of paper and you can bring yourself to a central point where your only focus is the page. And that’s really special.”

Brent Holmes and other artists, whether it is their profession or a hobby, have their own reasons for making art. Sometimes they make it for themselves. All it takes is an idea and some materials to work with. Retired USPS worker Beverly Neas, who moved from Boston to Nevada in 2005, submitted over 40 drawings to A Drawing a Day, the most of anybody. And she used simple materials from around her house – crayons, markers, and the back side of Christmas letterheads, mostly because a lot of stores were closed during the pandemic and she had to make do with what she had. When she ran out of paper, and more stores opened, she went out and bought white light-weight card stock to work with. Her straightforward pencil sketches, with a dash of color, depicted things that look interesting to her, like people, pets, and food. For the A Drawing a Day prompts she used her imagination. Even though she hadn’t drawn anything in over fifty years, her sketches received much admiration. The Marjorie Barrick Museum’s director, Alisha Kerlin, even bought one of them from her. “You know, and I do see other people’s artwork out there, and they’re so creative and talented,” Neas says. “So, it just amazes me that, you know, anybody is interested in what I’ve drawn. But it’s basically been just for me, and it’s been fun.”

As for the aliens, how would I personally explain art to them? There is no one correct answer. But if I were to take the advice of the artists who were asked this question, and combine it all into one response, I would suggest doing this: Start with something simple. Teach them about basic shapes and expand the discussion to other disciplines. Show them videos about artwork. And give them materials to play with. Then take them outside and show them all the shapes that exist in the real world. Take them on a field trip. Introduce them to artists and let them hear their stories. Show them what artwork looks like in all its forms and let them experience the transmission that takes place between artist and viewer. And then, if they are inspired by what they see, if they feel compelled to create, let them go out and gather the materials they need to begin making art on their own. And finally, coming from me, I would tell them to have fun with it.

Top photo: Lonnie Timmons III/UNLV Photo Services