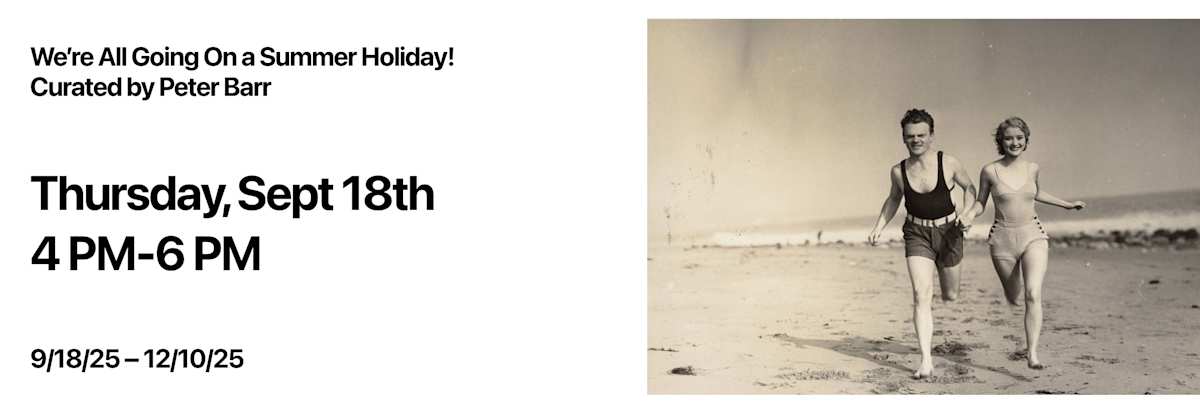

We’re All Going On Summer Holiday!

- September 18, 2025 - December 10, 2025

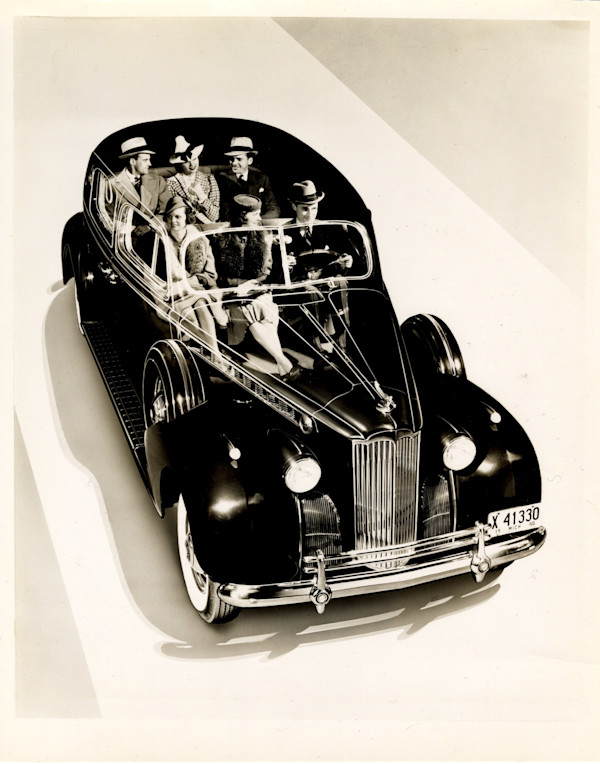

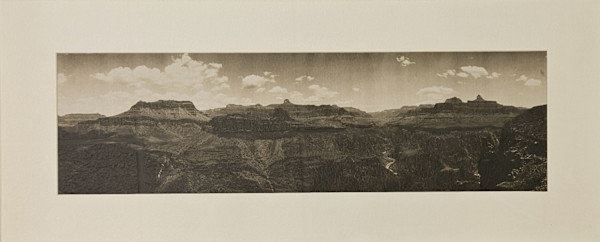

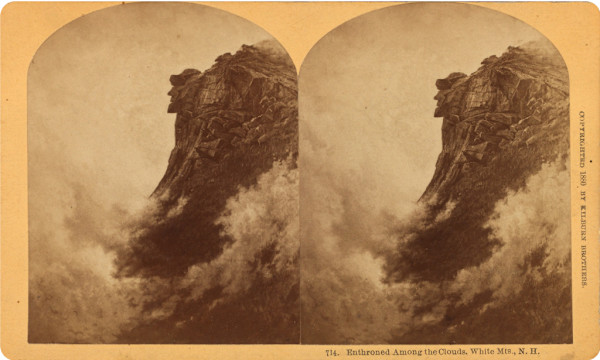

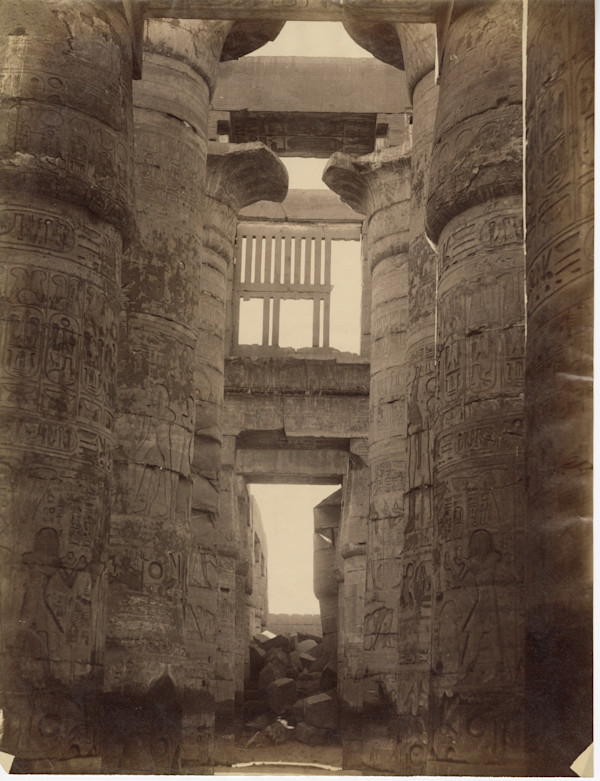

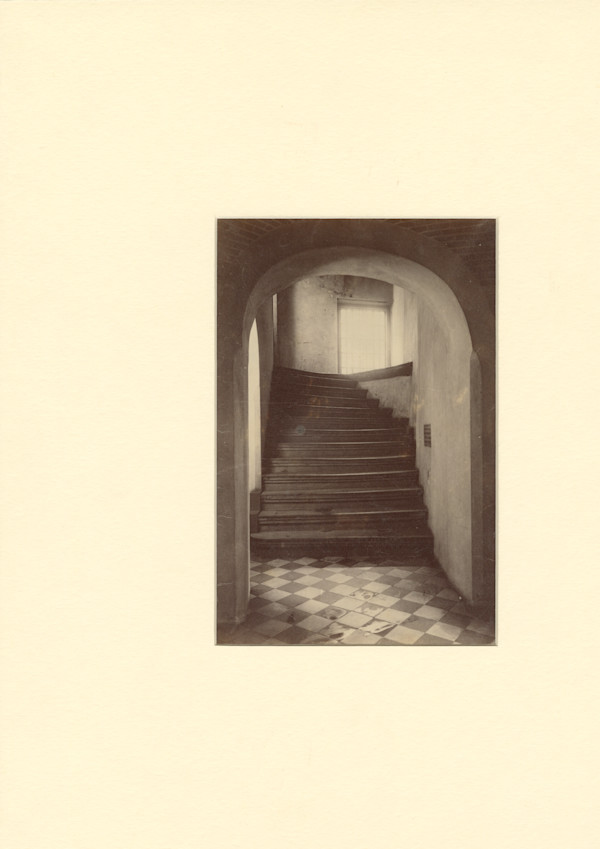

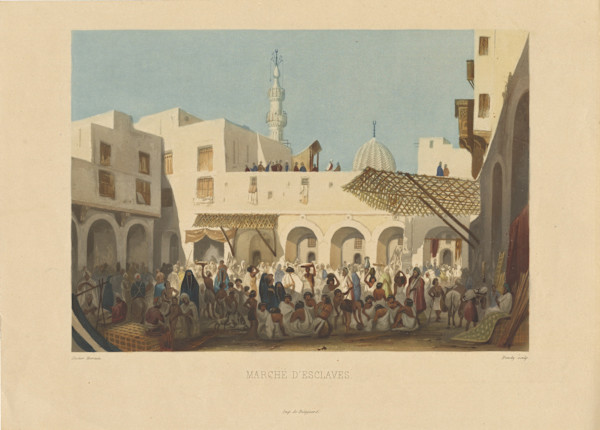

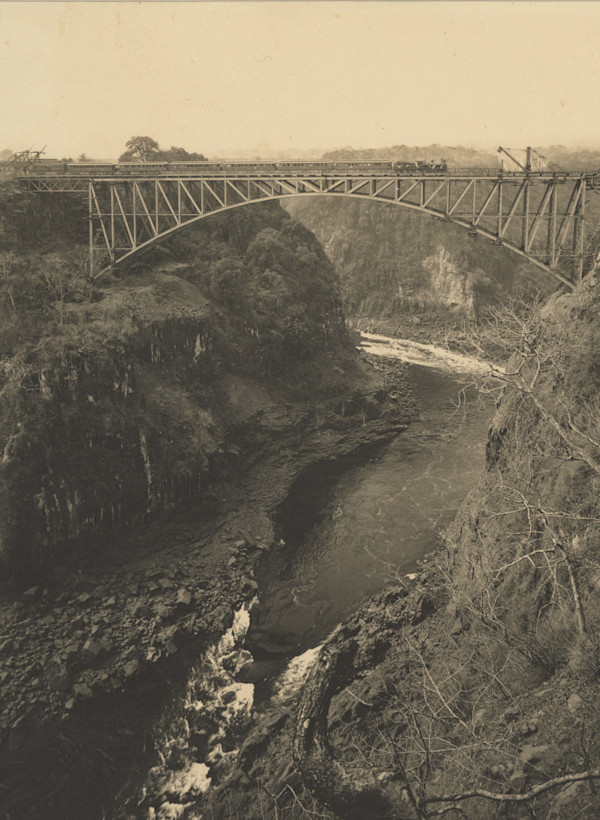

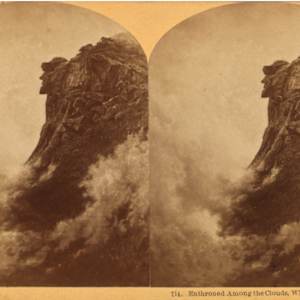

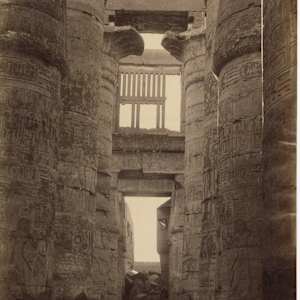

When first looking through the Rodger and Carolyn Kingston Collection of Vernacular Photography, I was immediately struck by its amazing range of informal beach scenes and images of picturesque landscapes, historic monuments, and awe-inspiring architectural details. Then suddenly, out of the blue, while thinking about these pictures, I was reminded of the title-song from the 1963 movie Summer Holiday. This exhibition adopts that song’s opening line, “We’re all going on a summer holiday,” as an invitation to travel the globe imaginatively and vicariously through these extraordinary images.

I selected and arranged these photographs primarily to encourage travel. Admittedly, physical travel comes with unavoidable challenges, including high costs, environmental impacts, and potential health risks. Yet, it also offers some remarkable and worthwhile rewards. Jessica Koehler, in her October 2024 Psychology Today article, “The Transcendent Power of Travel,” explains that excursions to distant places offer a variety of profound and lasting benefits, including a greater sense of self-confidence, openness to new ideas, and enhanced empathy and understanding toward others. In addition, even mediated travel—as afforded by this exhibition—has the power to boost one’s happiness and reduce stress simply by taking a break from the routines of daily life.

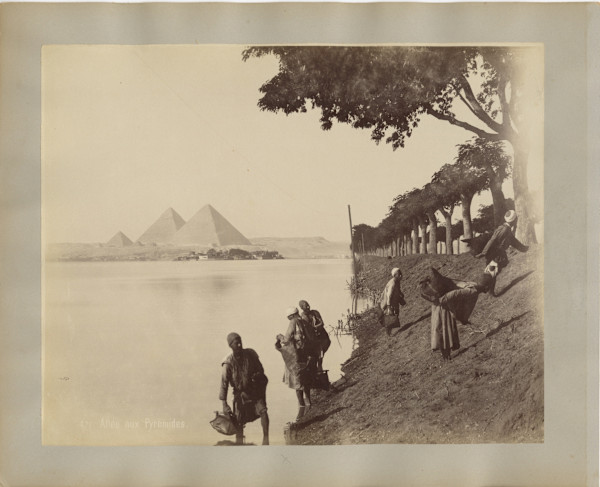

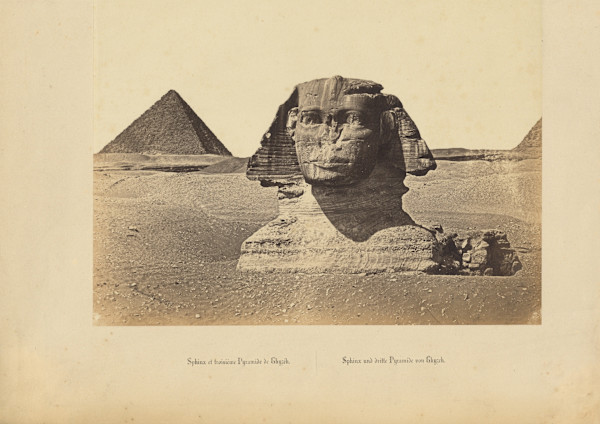

I also hope this exhibition will encourage you to recognize the diverse meanings offered by photographs. A photograph’s content, although seemingly objective and real, has a way of taking on unexpected connotations and associations that can vary from person to person, moment to moment, and place to place. In his 1980 book, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, the French philosopher Roland Barthes referred to the recognizable aspects of nearly every photograph, those aspects that draw us in and invite our scrutiny, as their “studium.” For example, in Resting Bedouins near the Great Pyramid of Giza, in the top third of the image we see Egypt’s world-famous Pyramid of King Khufu set against a cloudless pale blue sky. In the middle distance, there are sandy mounds, scraggy shade trees and towering palms as well as tiny structures that are dwarfed by the enormity of the pyramid. In the foreground, set against a sea of desert sand, appear stately Bedouins and their majestic camels. All of these things, or rather images-of-things, constitute the “studium” of the photograph because they are the familiar and culturally significant features of the image that invite our consideration.

Yet, the meaning of this photograph—and, indeed, of all photographs—can be surprisingly subjective. Each image has an ability to stir rather eccentric and personal reactions. For example, as an American art historian, the image of the pyramid arouses in me a yearning to move in closer and to see for myself the way the massive tomb epitomizes ancient religious beliefs. I want to see the structure’s careful alignment with the Earth’s compass points and its massive stacks of stones pointing upward toward the sun-god Ra. Yet in others, including modern people of the Middle East and North Africa, this photograph’s touristic depiction of Arabs might provoke feelings of annoyance or frustration because it could reinforce dangerous stereotypes. For example, the resting Bedouins might remind them of the remarkable scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark, when Indiana Jones, instead of engaging in a lengthy sword fight, pulls out a gun and shoots a Tunisian swordsman dead; this scene suggests that people from the “Orient” are outmoded and easily subdued by the shock-and-awe tactics of “Westerners.” Still, for others, this photograph might arouse a deep sense of melancholy when remembering a recently departed loved-one who once proudly shared with them their travel photographs of the Holy Lands. Barthes refers to such subjective connotations as a photograph’s “punctum,” a term that suggests that, even in their smallest details, a photograph can puncture or pierce the heart.

The title of this exhibition offers a useful metaphor for the changing meanings of vernacular culture since the phrase, “We’re all going on a summer holiday,” has taken on a variety of different readings over time. The original 1963 British film starred the wholesome balladeer Cliff Richard (Don, a bus mechanic), who by the film’s end proposes marriage to Deborah, who was played by the American actress and dancer Lauri Peters. They are joined on their journey by a group of attractive young co-stars who offer charming moments of comic relief as they travel together through Europe in a converted red double-decker bus. Along the way, they send home postcards of historic monuments, and they sing, dance, and romance among some of Europe’s most iconic sites, including the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, the snowcapped Swiss Alps, and the Acropolis in Athens. This cheerful and lighthearted film delighted audiences in 1963 with its upbeat optimism, becoming the second highest-grossing British film that year, topped only by the James Bond feature To Russia with Love. In addition, it produced five chart-topping hits, including the title track sung by Cliff Richard and the Shadows, which spent fourteen weeks on the charts and three weeks at number one.

By 1978, however, after years of economic instability and changing social norms, the upbeat optimism of the early 1960s had waned. That year, the British New Wave singer-songwriter Elvis Costello grabbed the film’s familiar line, “We’re all going on a summer holiday” for an angsty and aggressive tune, “The Beat.” Costello’s lyrics start with that familiar phrase but then underscore the hollow promise of love and happiness in Summer Holiday. He does this by conflating Cliff Richard’s widely reported aversion to marriage with his fall from the charts, suggesting that his personal life may have influenced his popularity after the rise of the Merseybeat musicians of the mid-1960s—such as the Beatles, Gerry and the Pacemakers, and The Dave Clark Five. His tune rhymes “machinery” and “scenery” to suggest that Richard (Don, the mechanic) was too distracted by the film’s beautiful locations to “complete” his relationship with Deborah:

See your friends, walking down the street.

See your friends, never quite complete.

See your friends, getting under their feet.

Oh, I don’t wanna disease you.

But I’m no good with machinery.

Oh, I don’t wanna freeze you.

Stop looking at the scenery.

. . .

I don’t go out much at night.

I don’t go out much at all.

Did you think you were the only one who was waiting for a call?

On the beat.

Then, less than a decade later, the chorus of “Summer Holiday” reappeared in "Holiday Rap” by Dutch musicians MC Miker G & DJ Sven, whose rhymes mention their plans to ditch high school in Amsterdam and pursue stardom in London, New York and Hollywood. With its low-fi production and obvious references to Madonna’s 1983 smash hit “Holiday,” their music video was given the dubious honor of being named Much Music’s “Worst Video of 1987”! More recently, in 2019, the 1963 film’s soundtrack was revived yet again when the UK Government's Drink-aware campaign adapted the title track of Summer Holiday for its "No Alcoholiday" initiative, which used radio advertisements and videos to encourage drink-free days. The song’s persistent reinvention over the last sixty years underscores its adaptability to new artistic contexts and interpretations, much like the photographs in this exhibition.

So, please enjoy this virtual journey! As you look over these images, bring with you your own imagination and lifetime of experiences and associations. What memories, emotions, judgements, or pangs of desire do these photographs awaken in you?

Peter Barr, PhD,

Professor Emeritus of Art History