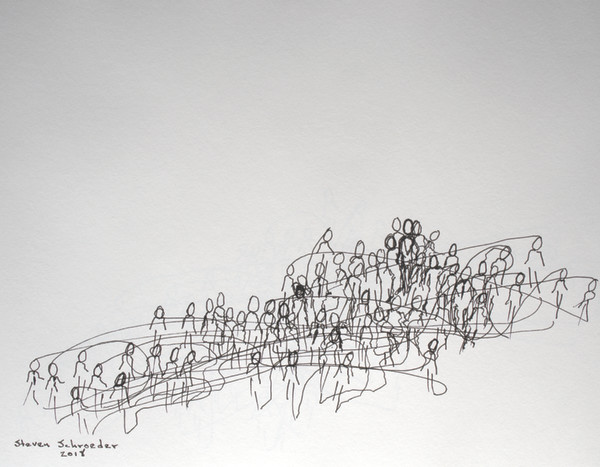

“Transfiguration” begins with an event recounted in each of the Synoptic Gospels where Jesus takes Peter, James, and John up on a mountain (Mount Tabor by tradition) where he is transformed and they see him with Moses and Elijah. I am particularly taken with the version in Luke 9:28-36, because it most explicitly connects Peter’s not knowing what he is saying but saying it with all three of the disciples who, as the story goes, witnessed the event and said nothing of it at the time. (Mark’s emphasis on fear as one of the reasons they said nothing – they were so afraid that they didn’t know what to say – is also on my mind as I think about the painting.) What strikes me – and what I hope to evoke in this work – is the momentary character of the change, the narrowness of the opening for light, and the foolishness of trying to make it permanent. (There is no surer way to kill a moment than to freeze it.) A person (in this case Jesus) is singled out as a flash of light that changes everything and then is gone. But, of course, if everything changes, that flash of light leaves a trace; and this always leads me to Leonard Cohen’s brilliant variation on Emerson: “There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.”

light like desire

never knows

when to stop,

takes color

in. endlessness

dazzles so

you don't see

nothing.

it leaves you

blind, starving

for one blue

fault imagination,

not light,

might

squirm through

to shed something

not white

on nothing

uncontained, right

before your eyes.

included in the 2018 Liturgical and Sacred Art Exhibit, Springfield Art Association, Springfield, Illinois.