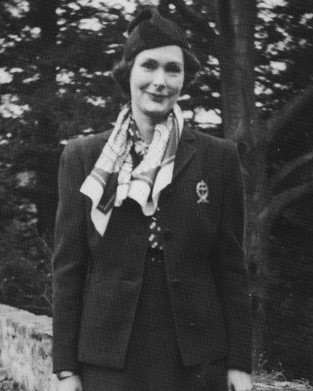

Caroline Ferriday - Godmother of Ravensbrück Survivors

Born: July 3, 1902, New York City, New York, U.S.A.

Died: April 24, 1990, Bethlehem, Connecticut, U.S.A.

Caroline Ferriday was an American humanitarian who dedicated her life to supporting survivors of Nazi camps, bringing them medical care, hope, and justice.

Caroline Woolsey Ferriday was born on July 3, 1902, in Bethlehem, Connecticut. She was the only child of Henry Ferriday, a New York dry goods merchant, and Eliza Woolsey Ferriday. Her family purchased a summer home in Bethlehem in 1912, which later became the Bellamy-Ferriday House & Garden. Caroline spent her winters in New York City and her summers in Bethlehem, where she developed a lifelong love for gardening and a strong sense of responsibility to help others.

As a young woman, Caroline pursued a short acting career on Broadway before turning her attention to service. She began volunteering at the French consulate in New York City during the 1930s. Her father had lived in France as a child, and his influence gave Caroline a deep love for French culture. This devotion to France would shape much of her life’s work. When World War II began, Caroline threw herself into efforts to support the French Resistance and to help war orphans. By 1941, she joined France Forever, the Fighting French Committee in America, and worked closely with French leaders who were determined to stand against Nazi occupation.

After the war, Caroline’s dedication only grew stronger. She began working with the National Association of Deportees and Internees of the Resistance (ADIR), an organization founded by French women who had survived German concentration camps. It was through ADIR that Caroline learned of Ravensbrück, a women’s camp in northern Germany where thousands of prisoners from across Europe were forced into slave labor and subjected to brutal medical experiments. Beginning in 1942, Nazi doctors cut open the legs of young Polish women, broke their bones, and infected their wounds with bacteria to mimic battlefield injuries. These women, many of them students, came to be known as the Lapins, French for “rabbits,” because they were treated like laboratory animals.

Caroline was horrified by the stories of suffering. Many of the women still carried deep scars, infections, and disabilities years after the war. She decided to act. In the 1950s, she became the U.S. liaison for ADIR and began campaigning for aid. But the West German government refused to compensate the Polish victims, arguing that they had no diplomatic ties with Poland, which was then behind the Iron Curtain. Caroline knew she needed to raise awareness in America.

In 1958, she persuaded journalist Norman Cousins, editor of The Saturday Review, to write about the Ravensbrück survivors. His articles captured public attention and generated donations to bring 35 of the women to the United States for reconstructive surgery and medical treatment. Dr. William Hitzig and other American doctors volunteered their time, while host families welcomed the women into their homes across the country. The trip not only improved the women’s health but also gave them a sense of hope and dignity.

Caroline personally traveled to Warsaw to meet the survivors, who came to adore her. They called her “godmother” and wrote letters to her addressed “Ma Chère Marraine” (“My Dear Godmother”). Survivors like Jacqueline Péry d’Alincourt, Geneviève de Gaulle, Anise Postel-Vinay, and Germaine Tillon, women of the French Resistance who had endured Ravensbrück, praised her generosity, loyalty, and courage. Caroline also worked to ensure that justice was done. She pushed for harsher accountability for Nazi doctors, including Dr. Herta Oberheuser, who had resumed her medical practice after prison. Thanks in part to Caroline’s advocacy, Oberheuser’s medical license was revoked in 1960.

Her efforts, along with those of Benjamin Ferencz, the former Nuremberg prosecutor, eventually led West Germany to provide financial compensation to victims of Nazi experiments, not only in Poland but in other Eastern Bloc countries as well. For her tireless work, Caroline received three medals of honor from the French government, including the prestigious Legion of Honor.

Caroline Ferriday passed away on April 27, 1990, leaving her Bethlehem home and gardens to Connecticut Landmarks. Through her dedication, compassion, and determination, she ensured that the voices of the Ravensbrück survivors would not be forgotten. Today, she is remembered not only as a philanthropist and activist, but as a true friend and champion of justice for women who had endured unimaginable suffering.

References:

Caroline Ferriday Collection - USHMM COLLECTIONS, collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn508306.

“Caroline Ferriday.” Saving the Rabbits of Ravensbrück, www.rememberravensbruck.com/caroline-ferriday.

“A Godmother to Ravensbrück Survivors - Connecticut History: A CTHumanities Project.” 11 Oct. 2023, connecticuthistory.org/a-godmother-to-ravensbruck-survivors.

Keywords:

Justice, Wartime, Courage, Generosity, Responsibility, Selflessness, Make a Difference, Stand Up for Your Beliefs

Explore ARTEFFECT projects about this Unsung Hero:

Caroline Ferriday Artworks

View Discovery Award projects about this Unsung Hero:

Caroline Ferriday - Discovery Award 2019

- Collections: Art Gallery, Unsung Heroes